Analivia Cordeiro, bianca turner e Selva de Carvalho | Fauna, Flora e Primavera: Curated by Fernando Mota

Past exhibition

Overview

“For a long time, we were tricked by the story that we are humanity. During that time – while the wolf doesn’t come – we became more alienated from this organism we are part of, the Earth, and we began to think that it is one thing and we are another: Earth and humankind

Ailton Krenak – Ideias para adiar o fim do mundo

“There are hands and spiders, the difference is only in the way that they caress…”

Lygia Fagundes Telles - Ciranda de Pedra

Stories, and histories, have been told for millennia in a wide range of ways – written, oral, performative, and many others. Likewise, stories are retold, reinvented and reinterpreted with the passage of time. Thus, when we say “the history of this and that,” or “the story is about…,” we are choosing one among many possible versions. Based on this thought, the exhibition Fauna, Flora e Primavera [Flora, Fauna and Merryweather] presents a new reading of the history of the body, of nature, and of the relations between them based on their confluent movements.

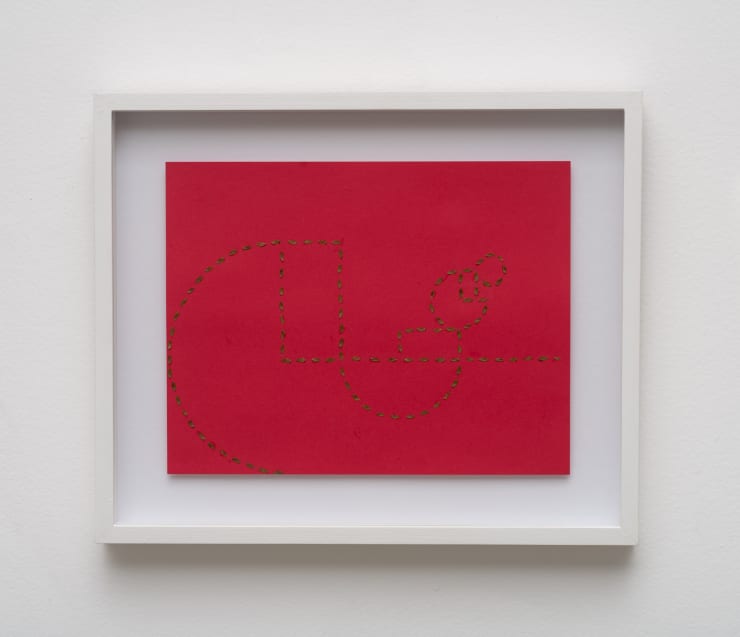

For decades, Analivia Cordeiro has investigated the possibilities of corporal language, through a wide range of works in different formats, including video, performance, and photography. The works featured in this exhibition, selected together with the artist, are from different moments in her career, ranging from historical works such as M3x3, the first work in video art/dance in the history of Brazilian art (1973), and Slow Billie Scan (1987), a revolutionary work at its time for its experimentation with the body and technology, to more recent works, such as Re-construct (2020) made during the COVID-19 pandemic, and Small Talk (2022), a work made in partnership with artist and dancer Gissauro and presented here for the first time. In the context of the exhibition, M3x3 is presented in its original (square) format on an old-fashioned CRT television in the center of the main room of the modernist house, bringing us nostalgically to a premonitory past: the bodies of the moving dancers fused in the rigidity of the 3x3 matrix of the computerized scenario, both in black-and-white, point to a reduced world without nuances, without the middle, a conflict between freedom and programming, the organic versus the artificial, the dilemma of the body coexisting with the machine. Slow Billie Scan reveals the new world of communication in the digital era, the possible effects and developments with the new technologies: the video shows a transmission of art by way of the slow-scan (SSTV) method between the Museu da Imagem e do Som of São Paulo and Carnegie Mellon University, in Pittsburgh, in which the morphology of the bodies on the screen breaks apart according to the slow transmission of the file, while new mutant bodies form due to the process. Re-construct is a series of collages of natural seeds on colored papers, forming geometric designs that allude to Brazilian concretism and to the movement of the recomposition of nature. The second part of the work is a video with the same elements, in which the seeds move on the papers by a breath of air, simultaneously emphasizing the fragility of life and the natural and instinctive discipline of the body. Homo Habilis II (2006) has the same structure of thought, based on drawing and collage made with four hands – those of the artist and her son Thomas when he was twelve years old – later completed with a short video that presents the eternal human conflict between war and peace, while nature participates as a witness. Small Talk operates as an anecdote of the show’s main plane, in both its unpretentious format as well as its light and good-humored presentation: two bodies dressed in gray dance freely on a small tablet screen, alongside small photographs of the video. The detail is that the socks are colored, symbolizing the need for the autonomy of our feet, of the paths that we choose to tread. Analivia Cordeiro’s participation in the exhibition is capped off by a series of photographs taken by the artist herself in 1975 at a Kwarup ritual, of the indigenous Kamaiurá people, in the Upper Xingu region, printed on dry leaves within cylinders suspended from the ceiling of the gallery’s pavilion – they are images of people in movement in everyday life, an anthropological trend within the artist’s research. Also as a highlight in the show we selected a group of photographs of Analivia’s body at different phases of her life, recorded by photographer Bob Wolfenson over the years, contemplating the natural change, vivacity and flexibility of the human body.

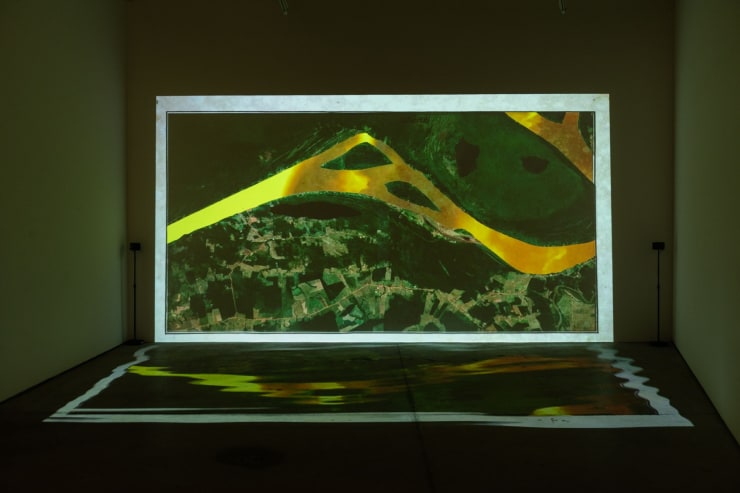

The artist bianca turner is present in the show with three works. The video Encobrimento, located in the house’s basement, narrates a Babylonian myth of Pherecydes of Syros concerning the ceremony of marriage between Heaven and Earth, superimposing cartographies of the period of Portuguese colonization of Amerindian lands, in which the process of territorialization is perceived as a principle and an action linked to patriarchy, while the appropriation of the Earth is related to the masculine domination over the women’s body, silencing its original nature and renaming its surface through impositions. The same cartographic research resulted in the work ecos, made in partnership with South African artist Neo Muyanga, a brand-new audiovisual installation that concludes the exhibition at the end of the gallery’s pavilion (a separate text about this work is available near the work itself). Also in the pavilion, the work Palingenesia – a word that comes from the Greek palin (many) and gênesis (birth) – alludes to the idea of reincarnation. It consists of a carousel of empty slides that project only light on the wall in a continuous rhythm, simultaneous with a second projection that overlays the illuminated frame with the image of a pulsating human heart, which can be seen in the transitions from one slide to the next. The amplified sound of the heartbeats underscores the power of nature within our bodies.

Selva de Carvalho is the third “fairy” of this story… all the artist’s works featured here are entirely new, including the installation Lacraia é fogo [Scorpion Is Fire] which refers to the cycles of life, conceived especially for Burle Marx’s garden at the center of the gallery, in which the fabric and ceramic scorpion passes through plants and along the ceiling throughout the space, in direct dialogue with the place’s architecture and nature. In the entrance room we see Medula de Medusa [Medusa’s Spinal Cord], a sequence of fabric sculptures with drawings and embroideries, pierced by a suspended wooden filament attached to the ceiling, thus forming an installation of floating bodies. The “spinal cord” symbolizes the resistance, the adaptations and the metamorphosis of the bodies in nature. In the back garden, between the house and the pavilion, another set of sculptures by the artist is scattered on the ground: Éramos palmeira [We Were a Palm Tree] consists of six bodies of palm leaves and cotton fabrics staked directly in the ground, an installation that counterposed Medula de Medusa, in its earth-grounded and nonlinear presentation. Last but not least, there is the work Corpo Chora Coral [Body Cries Coral], a coral made of fabric with papers, embroideries and drawings, on the wall opposite from bianca turner’s “luminous heart,” establishing a dialogue between the vital organ and the essential organism for marine life.

The show’s title refers to the fairies of the fairytale Sleeping Beauty, which has appeared in various versions over the centuries: the original story from 1634, titled Sun, Moon and Talia, by Giambattista Basile, was the basis for the classical version by Charles Perrault, from 1697, in which there are seven fairies and the end is not exactly as it is told today, as there is a second part after the royal wedding; in the renowned version of the Grimm brothers, from 1812, there are twelve fairies and the end is briefer; the adaptation by Tchaikovsky for the ballet, in 1890, transfers the name of the princess’s daughter to the princess herself, previously nameless; the cinematographic version by Disney, from 1959, maintains the princess as Aurora and reduces the number of fairies to three, now named Flora, Fauna and Merryweather. In this last version, possibly the most well-known currently, the three fairy godmothers give gifts to the princess on the day of her christening and are later responsible for raising, educating and protecting her throughout her childhood and adolescence. We thus see, literally, that Flora, Fauna and Merryweather are Aurora’s protectors. We now interpret together, beyond the context of the children’s tale, using the scientific meaning of the words that we learn in biology: Flora (the set of plants of a region), Fauna (the set of the diversity of animals in a region) and Primavera [the name of the third fairy in the Portuguese translation of the Disney film, which means the season of the year “spring”] which comes from the Latin primo vere, meaning literally “the first of summer,” responsible for altering the behavior of plants and animals due to the climatic change favorable to flowering and reproduction. These are the three protectors of Aurora (the dawn, the morning light). Completing the analogy between science and literature: the fairies are not only responsible for a single person, they also become the protectors of tomorrow. However, who is there to protect the fairies?

If a simple fairytale went through so many transformations over the years, why can’t we also modify the narrative of our own histories as “Terrahumanity”? What other movements should we make as singular collective bodies to prosper as a single, healthy and sustainable body? The philosopher Félix Guattari, in his essay The Three Ecologies (1989), says that “[there will follow] a reconstruction of social and individual practices which I shall classify under three complementary headings, all of which come under the ethico-aesthetic aegis of an ecosophy” – as a simplistic and largely shallow summary of the French intellectual’s thought, we can say that changes in social behavior and human thought are necessary for us to reevaluate environmental questions and to advance in a more balanced way as society in the 21st century. That is, the relations that we establish with nature inevitably include the relations that we develop as human beings: the search for a life in harmony with the natural environment is directly linked to the contemporary socioeconomic and cultural structure that is deteriorating at every moment. There is no fairy godmother that can give us a happy ending if we do not change the course of our history. Once upon a time, we were, and hopefully, at another time, we will still be.

Fernando Mota

Installation Views

Works