Afonso Tostes | Ajuntamentos

In recent years we have witnessed a profound historical revision conducted by an anticolonial point of view that seeks to understand the constitutive epistemological violences of art history. In a very singular way, without mimicking formal or discursive mannerisms, the exhibition Ajuntamentos [Joinings], by Afonso Tostes, echoes this movement of change that marks the present. And why in a singular way? Because, in Tostes’s work, what takes place is not a denial of the Western canon, but rather the encounter of two rivers. On the one hand, the river whose waters form the set of works recognized by an official historiography, and, on the other, the river filled with the knowledge of traditional peoples. This is one of the ajuntamentos forged by the artist.

The installation that opens the show presents the balance between cords marked by the scattered presence of a series of elements collected by the artist on his trips around Brazil. The work is inspired by the clotheslines seen in riverside communities, while its various support points bear indices that Tostes found in his ramblings along the country’s borders. At the ends of this work – part of a series called Linha do tempo [Timeline] – long rods made of sanded wood hang, in the shape of large pencils, associated to fragments of an old illustrated encyclopedia whose volumes the artist found by chance in the streets of Copacabana. The wood came from a demolished wattle-and-daub house in the interior of Minas Gerais, therefore bearing the memory of a vernacular architecture deriving from the blend of Portuguese, indigenous and African techniques. Thus, the fragments of the encyclopedia that evoke an organization of knowledge characteristic of Western rationality are intermeshed with elements referring to another sort of knowledge, generated anonymously by popular knowledge.

The game of balance seen on the clothesline also takes place in the large wooden sculptures which allude to totemic forms. Here, fragments of tree trunks found in Ibirapuera Park are stacked atop one another in a fragile stability. To help maintain their balance, they are propped up by wooden strips and sculpted pieces that the artist calls bengalas [walking canes], which look somewhat like bones. Segments covered with different colors lend the pieces a pictorial dimension. As we approach these works, we are reminded of Constantin Brâncusi in his seminal gesture of taking the sculpture off from its pedestal. At the same time, a large part of these works is owing to an organic experience of the artist within the worlds at the fringe of so-called refined culture.

The vertical aspect of each of these works refers to the trees the wood came from, while their size invites us to a relationship that is not only visual, but also corporal. For their part, the ways by which they remain standing recall the ingenious solutions invented to prop up structural slabs or walls in cities in Brazil. And the use of colors is reminiscent of the paintings made by fishing communities on their boats with the aim of protecting them from storms, but which end up achieving a striking aesthetic effect. It should be noted that this dynamics of associations should not be read as a sort of instruction manual to be followed in one’s encounter with the work. Everything in Tostes’s work is far from literality. Just like the supports of these sculptures, the artist prefers to live in a fluid territory, without totalizing judgments, and closer to what Boaventura de Souza Santos called an “ecology of knowledge.”

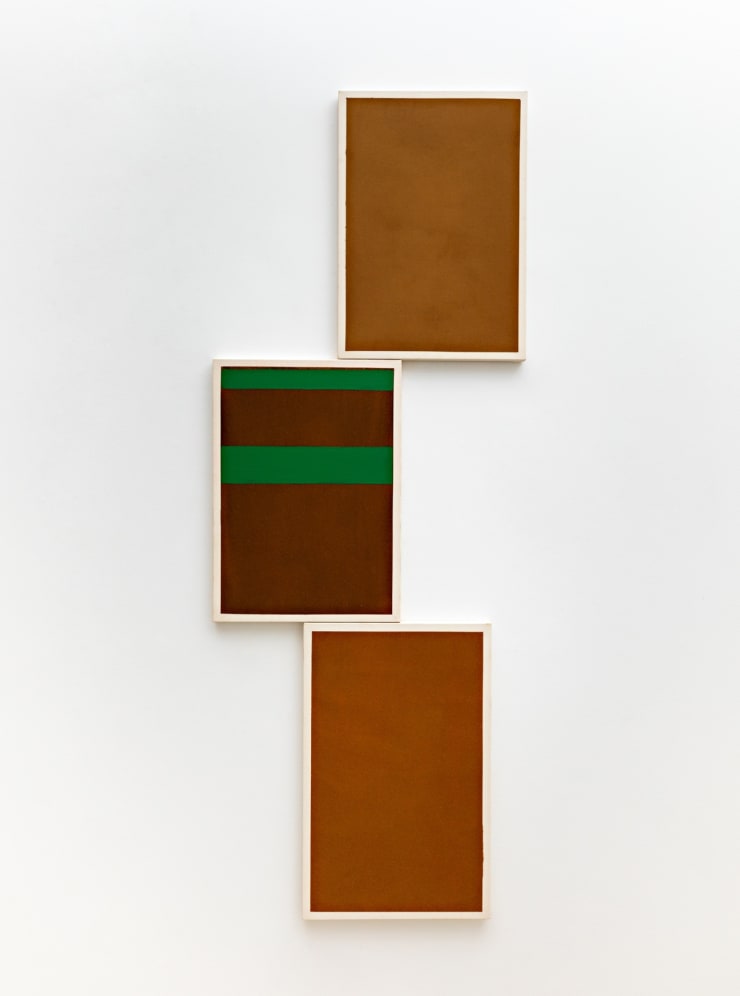

All the artworks gathered here were constructed from elements that were already in the world. This choice bears, obviously, an aesthetic meaning. Amidst an era marked by an excess of disposable beings, whose obsolescence is already planned at their origin, Tostes moves against the grain of this predatory scheme. Even the small canvases of the Reforma [Reform] series are the result of the artist’s attentive focus on what already dwells between the lines of the world closest to him. In this series, we see paintings whose “paint” is the sawdust resulting from the sanding of the sculptures. What was destined to be thrown away and forgotten, that which is microscopic when isolated but gains force as a collectivity, was carefully gathered over time, and kept, to be used on the surfaces of these monochromatic and geometric canvases. We also note how the paintings climb the wall, some of them supported atop others, as though evoking the movement of the sculptures.

The same historical moment that is witnessing the anticolonial epistemological shift mentioned at the beginning of this text is, moreover, that which is seeing the growth of reactionary waves whose common denominator lies in the idea of union by similarities and the rejection of alterities. Such a communion by resemblance involves a search guided by the notions of purity and exclusion. The ajuntamentos woven by Afonso Tostes over the course of his production bring us to the antipodes of that regressive movement. We stand in light of a gesture that is simultaneously poetic and political, which beckons for us to imagine a more polyphonic and solitary world – a world of many worlds.

Luisa Duarte