Empowering Certain Geometries

Cristiana Tejo

“What history or stories would we tell if, instead of a bone, which becomes an axe, which becomes a sword, which becomes a pistol, a cannon, a machine gun, and a bomb, we consider that the most important invention of humankind was the object made to contain other objects?” This is the question posed by anthropologist Ursula K. Le Guin in her book A Ficção como Cesta: uma Teoria [Fiction As a Basket: A Theory].¹ That is, if we could learn to admire baskets – their weaving and their function in the (gathering) society they gave rise to – rather than the axe or the spear, and consequently the world that was created based on objects that kill and subjugate, then what could we retell, remake or redo? A history of art based on the basket is perhaps a narrative in which the home, the affections and what nourishes and moves the artist are more important than awards, amounts, biennials and the résumé.

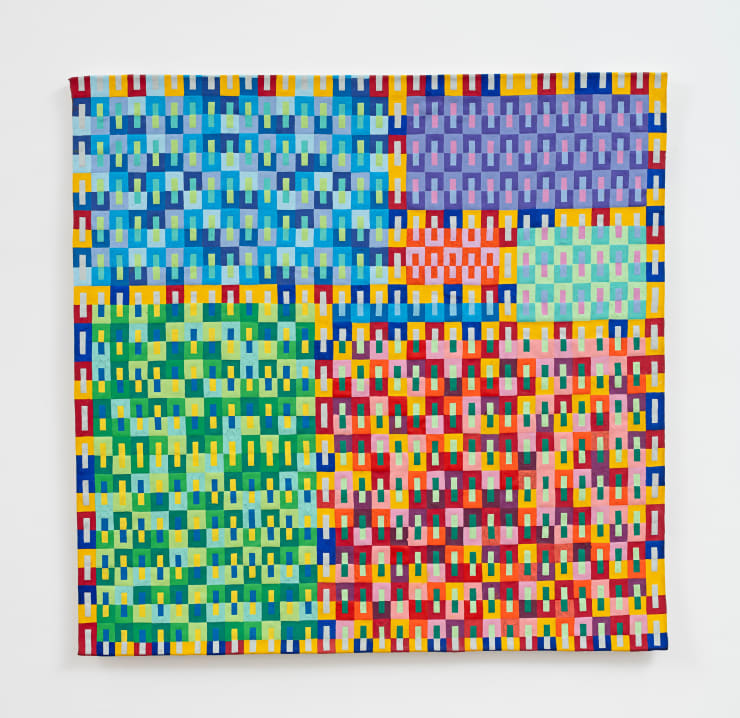

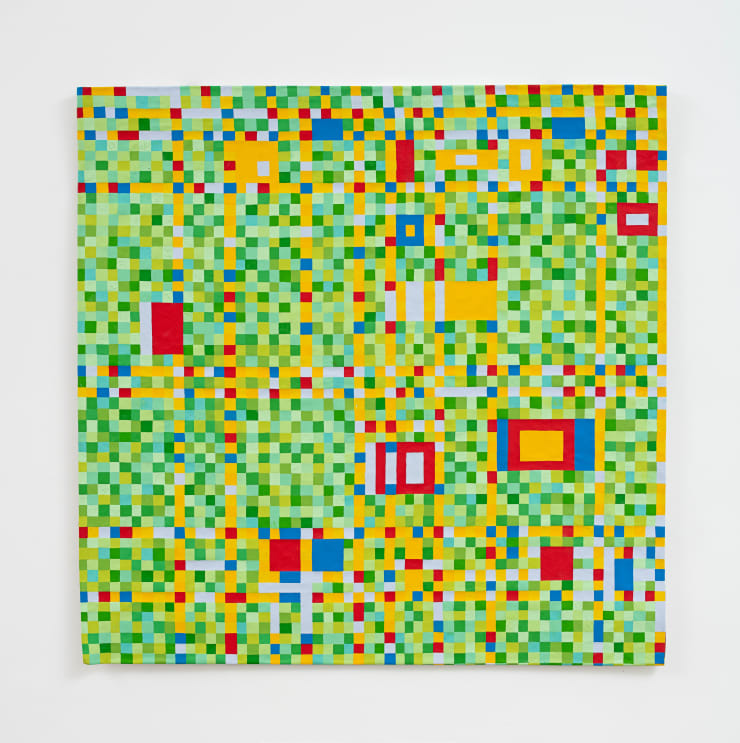

By making paintings with the addition of plant fiber – the basis of baskets, mats and houses of many of the many peoples who have existed since time immemorial in the territory that came to be called Brazil, and of many others who became part of it in the passage of centuries – Delson Uchoa spotlights weaving as the ancestral structure of this country. His paintings have always openly exalted his Northeastern origin, whether through the presence of the “strident” colors and lighting of Brazil’s Northeast, as pointed out by Paulo Herkenhoff, or through countless symbolic and textual references. His return to his homecity of Maceió, after many years in Rio de Janeiro, was essential for the artist’s aesthetic vocabulary to come fully into its own. There is always a sense of unease when we talk about the Northeast in a city like São Paulo. Perhaps because of the counterpoint between a place that exposes the oppressive structures on which the country was founded and the metropolis that tries to embody the dream (or illusion?) of being modern. But as Bruno Latour aptly observed, we have never been modern… Beneath the district of Liberdade [which means “freedom” in Portuguese] there lies the Pelourinho [whipping post] and the first houses of freed enslaved people in what was the fringe of a small village in colonial times. But if modernity is a march that trampled, massacred, erased and decimated, why do they want to be part of it?

Delson Uchoa’s painting is often a house, a skin, an inhabited painting. The geometry that structures much of his production in the last 20 years comes from the square patterns seen on the tiled floors of houses, a domestic geometry. The resin he uses as a basis in his painting ends up extracting the dust and residues of the house’s floor. The works featured here are based on other geometries, especially those present in Brazilian vernacular architecture, such as the oca (built of wood and straw), the dwelling made with wattle and daub (framework of interlaced thin branches daubed with clay or mud), the house made of rammed earth, as well as the platibanda-style houses of the Brazilian Northeast, a local rereading of an architecture from the Iberian Peninsula, supposedly from a Moorish origin. For people such as the Wayana, Tiriyó, Aparai and Yekuana, the outer covering of the arumã stalks resembles human skin; therefore, when woven, the fibers form the “skin” of the primordial woman as well as that of the fundamental supernatural beings.² The interweaving that Delson adds to his new painting thus refers to other houses and skins, other containers. It is a sort of cartography, a cultural and emotional localization of cities, elements, materials and patterns. Just as Piet Mondrian looks at the grid of New York’s urban layout and the circulation dynamics of the great city of the new empire, Delson Uchoa observes the geometric weave of the houses and the patterns of artifacts from the rural and backcountry regions of the Northeast, and paints their vibrations. But unlike Mondrian, who is astonished by the strange and the different, Delson dives fully into the essence of his own culture.

The rural and backcountry lands are characterized by the resilience of the human and nonhuman beings alike. Not much used in Brazil, the word agreste in Portuguese bears specific connotations related to the dry climatic conditions and soil of Brazil’s Northeast. An intense struggle is needed, however, for life to survive in this territory. Despite all the setbacks, beings and things sprout forth. In the history of art based on the basket it is this geometry that should be empowered, while not forgetting Mondrian.

¹ Le Guin, Ursula K. (2022). A ficção como cesta: uma teoria e outros textos. Lisbon: Dois Dias edições. [That book is the basis for the quotation given here, translated from the Portuguese. It should also be noted that, in English, Le Guin wrote about a “carrier bag,” while the book cited here, published in Portuguese, refers to a cesta (basket). In keeping with the various references to basketry in the present text, this English translation also retains the metaphor of the basket.]

² VELTHEM, Lucia Hussak van. “Trançados indígenas norte amazônicos: fazer, adornar, usar.” Revista de Estudos e Pesquisas, Brasília, v. 4, n. 2, pp. 117–146, Dec. 2007, p. 124.